Your ultimate home decor inspiration destination!

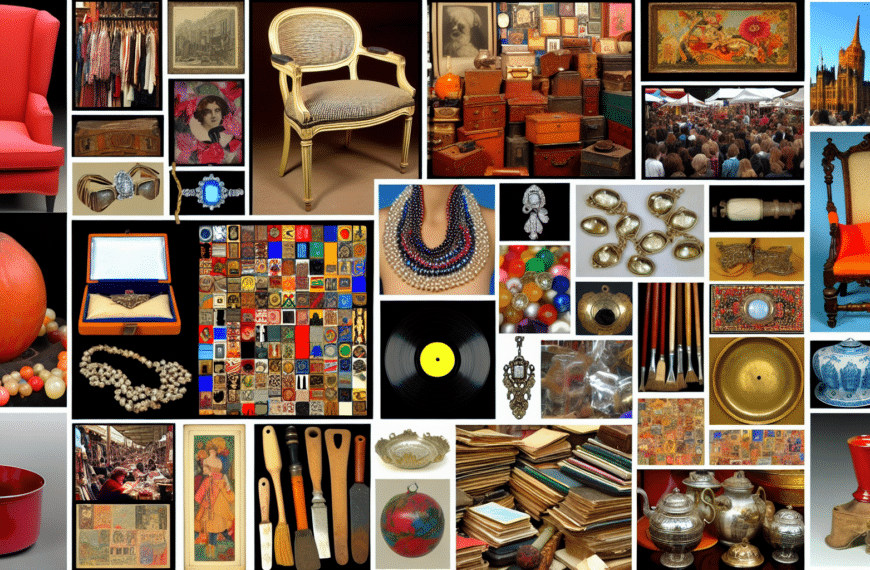

We’re excited to have you embark on this creative journey with us. Decor enthusiasts or novices, there’s something for everyone here – the latest trends, DIY how-tos, expert tips, seasonal decor ideas, and much more.

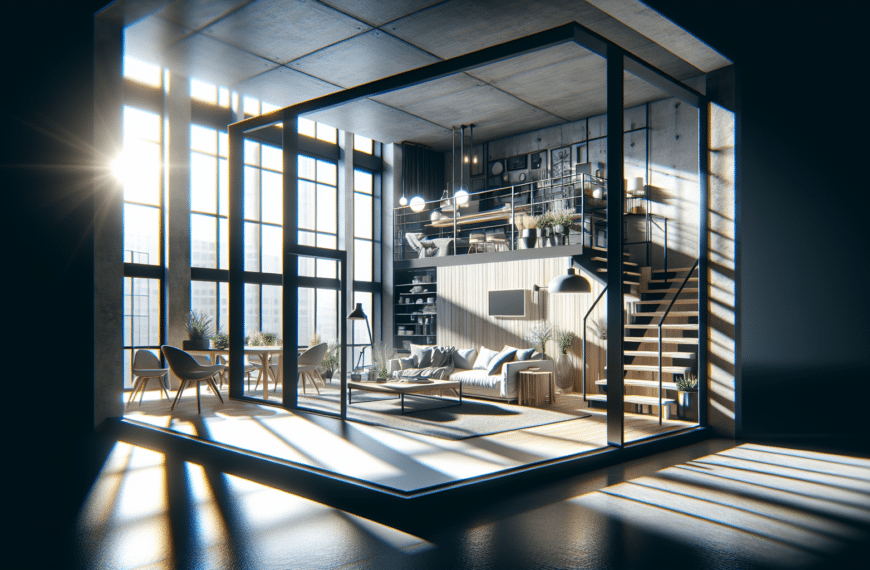

At ISGmag, we believe decorating is a form of self-expression. No matter your style or budget, we’re here to help you design your dream home. Discover a world of groundbreaking designs, innovative layouts, and stylish creations that speak to your unique taste.

So why wait? Dive right in and let’s create a space that’s not just a house, but a home you love. Welcome aboard the ISGmag experience and let’s make your home decor dreams come true, one room at a time!